101 - Particle Physics Edit Page

Contents

What is the world made of ?

Standard Model of Particle Physics

Beyond Standard Model

With the discovery of Higgs particle [1] , a complete set of particle physics system based on the standard model has been improved, which can explain all the observed particles and interactions. But in the process of exploring the universe, people gradually realize the existence of dark matter and dark energy, and have a strong interest in it.

In the process of human exploration of the universe, a series of studies on galaxies, galaxy clusters and cosmic microwave background show that our universe is a flat universe that is accelerating expansion [2, 3] . But in theory, the gravitational pull between matter in the universe prevents it from expanding all the time, unless there is other dark matter or dark energy. According to the observation data, we found that dark energy accounts for the majority of the universe, about 70\%, followed by dark matter, accounting for 27\% of the total energy density [4]. Dark matter is considered as a hypothetical particle, which does not participate in electromagnetic interaction, but in gravitational interaction. The interaction between dark matter and all known basic forces in the standard model is very weak, or even not at all. Therefore, the study of dark matter has become one of the hot spots in today’s physics [5, 6, 7] . As for what dark matter is, one hypothesis holds that dark matter is composed of weakly interacting massive particles (wimps), which can hardly be detected by detectors. The experiments on LHC can be used to find the detectable wimps related to the final state, and to limit the generation of low-quality wimps [8, 9] . In the experiment, the search for dark matter is usually to study the lost energy in the large Collider, and judge the possibility of the existence of dark matter by comparing with the theoretical calculation of neutrino final state in the standard model. This experimental method has higher requirements for the detector.

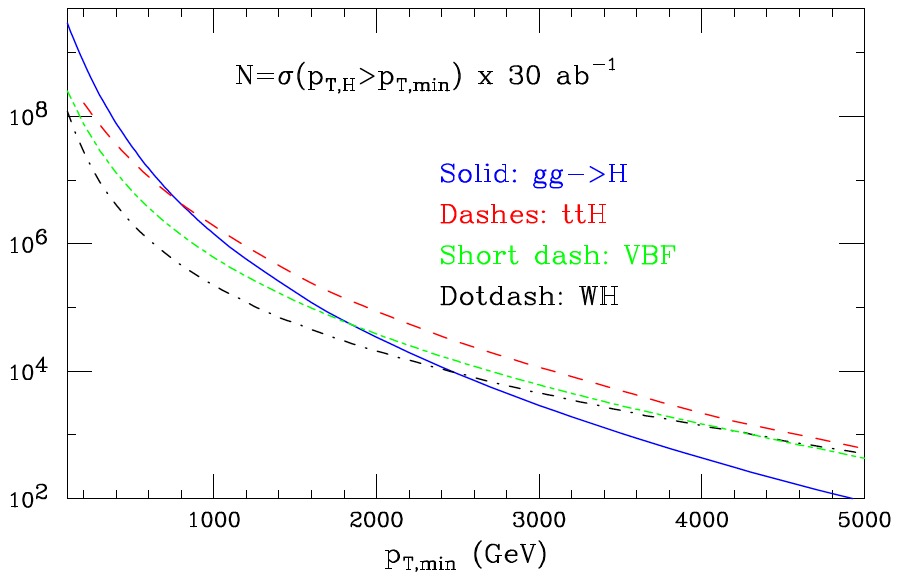

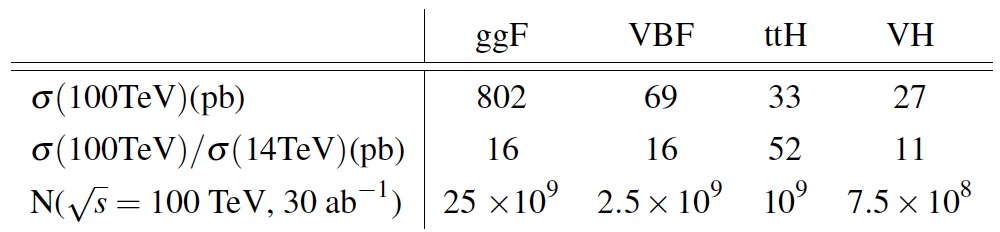

Many open problems of the SM are connected to the Higgs sector. For example, the stability of the Higgs mass [10] and of the Electroweak (EW) scale in general against UV-sensitive radiative corrections motivate the existence of new symmetries near the TeV scale. Their experimental methods can be direct, via the production of new particles, or indirect, via deviations of the Higgs properties from their SM predictions. The future circular hadron-hadron collider FCC-hh is expected to produce collisions at the center of mass energy of 100 TeV and to deliver an integrated luminosity of $30 ab^{-1}$. To complement the capabilities at the LHC and possible future e+e- colliders, the 100 TeV pp collider would provide a potential to explore the Higgs boson properties based on its extraodinary energy and integrated luminosity. At 100 TeV, the Higgs production rate increases by a factor 16 for gluon-fusion production (ggF) with respect to 14 TeV. At the FCC-hh the ttH rate increases by factor 52 with respect to the LHC, giving a total rate similar to gluon fusion production at the LHC.

Upper row: Cross sections at 100 TeV for the production of a SM Higgs boson in the gluon fusion (ggF), vector boson fusion (VBF), top pair associated (ttH) and Higgs-strahlung (VH) production modes. Middle row: Rate increase at 100 TeV relative to 14 TeV. Lower row: Expected number of Higgs bosons produced with an integrated luminosity of $30 ab^{-1}$. [11]

Upper row: Cross sections at 100 TeV for the production of a SM Higgs boson in the gluon fusion (ggF), vector boson fusion (VBF), top pair associated (ttH) and Higgs-strahlung (VH) production modes. Middle row: Rate increase at 100 TeV relative to 14 TeV. Lower row: Expected number of Higgs bosons produced with an integrated luminosity of $30 ab^{-1}$. [11]

Higgs decaying to invisible particles is an important component of the dark matter search. The search for Higgs decaying invisibly uses the $p_{T}^{miss}$ distribution since the $p_{T}^{miss}$ reflects the $p_{T}$ spectrum of the Higgs boson. The total Higgs production cross section is dominated by gluon fusion and vector boson fusion. However, at high $p_{T}$ the relative proportion of gluon fusion with respect to the rest of the other production modes is reduced, leading to the result that the VBF and the ttH have advantageous properties that allow for further signal background separation.

| The VBF production mode has the characteristic signature of two jets with relatively large $ | \eta | $. With the current 13 TeV searches, the VBF production mode is the dominant channel for the Higgs invisible search. The most powerful approach to searching for the Higgs invisible decay in this mode is to look for events with large missing transverse energy (above 200 GeV at current 13 TeV) and large di-jet pair mass $m_{jj}$. |

The search for Higgs decaying invisibly produced with pairs of top quarks is perhaps the most promising channel since the relative cross section is hugely enhanced with the respect to background processes when compared to 13 TeV Higgs production.

[1] Chatrchyan S, Khachatryan V, Sirunyan A, et al. Observation of a new boson at a mass of 125 gev with the cms experiment at the lhc [J/OL]. Physics Letters B, 2012, 716(1): 30-61. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0370269312008581. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2012.08.021.

[2] Astier P, Pain R. Observational evidence of the accelerated expansion of the universe [J/OL]. Comptes Rendus Physique, 2012, 13(6): 521-538. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1631070512000503. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crhy.2012.04.009.

[3] Riess A G, Filippenko A V, Challis P, et al. Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant [J/OL]. The Astronomical Journal, 1998, 116(3): 1009–1038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/300499.

[4] Pongkitivanichkul C, Samart D, Thongyoi N, et al. A kaluza–klein inspired brans–dicke gravity with dark matter and dark energy model [J/OL]. Physics of the Dark Universe, 2020, 30: 100731. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212686420304441. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dark.2020.100731.

[5] Jungman G, Kamionkowski M, Griest K. Supersymmetric dark matter [J/OL]. Physics Reports, 1996, 267(5): 195-373. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0370157395000585. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(95)00058-5.

[6] Bertone G, Hooper D, Silk J. Particle dark matter: evidence, candidates and constraints [J/OL]. Physics Reports, 2005, 405(5): 279-390. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0370157304003515. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2004.08.031.

[7] Feng J L. Dark matter candidates from particle physics and methods of detection [J/OL]. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 2010, 48(1): 495–545. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-astro-082708-101659.

[8] Buchmueller O, Dolan M J, Malik S A, et al. Characterising dark matter searches at colliders and direct detection experiments: vector mediators [J/OL]. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2015, 2015(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/JHEP01(2015)037. DOI: 10.1007/jhep01(2015)037.

[9] Malik S A, McCabe C, Araujo H, et al. Interplay and characterization of dark matter searches at colliders and in direct detection experiments [J/OL]. Physics of the Dark Universe, 2015, 9-10: 51–58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dark.2015.03.003.

[10] V. F. Weisskopf, On the Self-Energy and the Electromagnetic Field of the Electron, Phys. Rev. 56 (1939) 72, DOI: 10.1103/PhysRev.56.72.

[11] R. Contino et al., Physics at a 100 TeV pp collider: Higgs and EW symmetry breaking studies, CERN Yellow Report (2017) 255, DOI: 10.23731/CYRM-2017-003.255, arXiv: 1606.09408 [hep-ph].